Text: Julio Grosso Mesa (Film in Granada)

The executive producer of “As bestas”, a young Catalan of Grenadian heritage, celebrates her 20-year career in the film industry, collecting numerous awards and prizes for her latest work, including the Goya for Best Film and the César for Best Foreign Film.

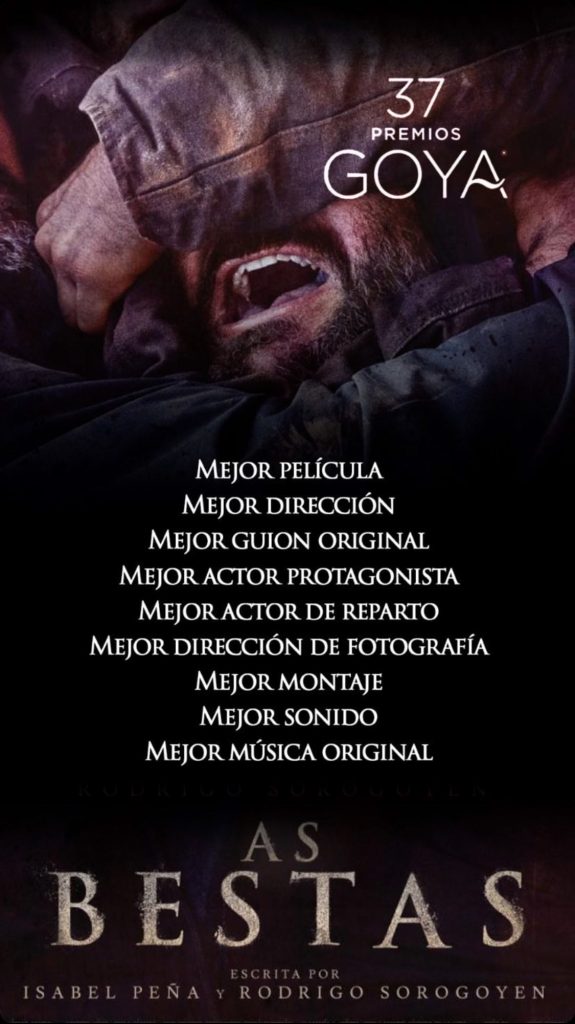

Before graduating in Audiovisual Communication from the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Sandra Tapia (Girona, 1983) had already worked on a set. It was as an intern on a Spanish film, starring Najwa Nimri and Luis Tosar, which would end up nominated for the Golden Shell at the San Sebastian Film Festival. Since then she has always worked on the production side, first as a production and post-production coordinator, since 2010 as executive producer, and finally as one of the four partners of Arcadia Motion Pictures, the small company behind big hits like Enrique Urbizu’s “No rest for the wicked“, Pablo Berger’s “Snow White” and Rodrigo Sorogoyen’s “As Bestas” -9 Goya Awards, 1 César, 2 Forqué, 3 Feroz and more than 6 million euros in box office-.

Sandra Tapia is also responsible for the discovery (and support) of some new authors, such as screenwriters Celia Rico and her amazing “Journey to a Mother’s room” and Marcel Barrena with “Mediterraneo: The Law of the Sea“. And she defends, when possible, the creative dimension of the producer.

Although she was born in Girona and works in Barcelona (curiously, on Ciudad de Granada street), Sandra has spent many summers of her life in Caniles, the Granada village where her parents were born, and where she and her twin sister Tania still have their teenage gang. She confesses that Granada is her “second land” and assures that “there are very few provinces in Spain that can offer such a diversity of landscapes and film sceneries”.

You started in cinema at the age of 21 as an intern in a production company, how did you immediately move towards executive production?

My first film was “Celia’s lives” by Antonio Chavarrías, starring Najwa Nimri, Luis Tosar and Daniel Giménez Cacho and I was still finishing my degree and I was taking exams during the day and shooting practices at night. Little by little, I realized that I wanted to be in the executive part and I wasn’t so interested in the shooting, even though it’s the most fun. I wanted to be in the decision making, because getting to shoot is the achievement of something that has been worked on, thought out, written, financed, rehearsed and designed by the crew chiefs and from there, I was moving towards executive production, which is what I really like.

Before becoming an executive producer, you have also been Production Coordinator, Postproduction Supervisor…

Yes, I’ve been a bit of everything. The good thing about working in small production companies is that they allow you to be at all levels of the process, from initial development to international sales, and you can learn from all those processes and accompany the films from the purchase of the rights to a novel to the last international festival or the last sales contract.

What does executive production give you compared to other production jobs?

We executive producers are a bit like the moms and dads of films, and I always defend the creative dimension of the producer. Many people think that we are only the ones with the money, but I defend that the origin of an idea can be multiple: myself seeing a theater play and buying the rights to adapt it to film, seeing the pitch of a project in an opera prima lab and thinking that there is talent and betting on it, or it can be rewriting a script. The idea of a film is the work of very few people: the screenwriter, the director, who are sometimes the same person, and the producer, who manage the film in year zero and decide where and how we are going to shoot it, with whom, and so on. Then, everything gets bigger with a huge family on set for several weeks, and finally, we return to the author, the producer and sometimes also the editor, in a relationship of intimacy. There is an exercise of absolute trust between the director and the producer, because I will want the best for that film and he or she will logically want the same. Producers are also a creative entity in films.

You have worked with established authors such as Pablo Berger and Rodrigo Sorogoyen. What is the difference between producing an auteur project and a more commercial one?

There can certainly be, but there are also differences between authors, because it is a human work, so each one has his or her own way of working and understanding cinema. I have almost always worked with auteur projects and I have had the freedom to decide the stories we wanted to tell, but the fact that it is auteur does not always mean that it is not commercial. “As bestas” has already reached 6 million euros at the box office. But I think the difference is in the person you work with and to whom you are answerable. But the success or failure of a film is not the box office but the dimension of that film. That is to say, if the objective of a debut feature is to have visibility at festivals, to win awards, to position the author to make a second film, and to make a moderate box office, success is already there.

How does “As bestas” become a great commercial success?

I always talk about “the perfect storm”. You have to prepare for it to happen. But sometimes it happens, and sometimes it does not. From the beginning we were clear with “As bestas” that it was a mature project, from a director who was in a very good moment of his career and we wanted an internationally prestigious route, because Rodrigo had already had his way in San Sebastian before. We worked hand in hand with the distributor and decided to show it and not be afraid that it would be seen a lot and that the “snowball” effect would grow. We went through Cannes, San Sebastian, Seminci, Seville, Sitges and all the important Spanish festivals and we left it at a peak moment to premiere very close to the awards campaign, so that it would have an impact and continue to trickle at the level of publicity in the media while it was alive at the box office and not on the platform, where it arrives on March 10. We wanted to claim the screen with a film that is not dubbed, spoken in three languages, with a casting not well known by the general public. There was a strategy behind all this. Now the film travels on its own and is very transversal. But this happens very rarely in life. It is not a coincidence. There is a lot of work behind it.

What has this promotion strategy been like?

There has been a big marketing campaign and a well thought-out positioning. On the promotion, marketing and distribution side we always work with the same enthusiasm and energy to make things happen, but it doesn’t always work the same way. Over the years I have learned to be a distributor because now we producers also risk a lot of money or pay for the release campaigns of the films, so I have become a distributor by force as well. It is a very unknown phase for people. The producer is now very involved in the marketing of the films. I am involved in the editing of the movie trailers. I have the creatives for the posters on my desk. I’m on the set generating materials with marketing in mind to create a narrative to be able to release the film. Since we are very small production companies that don’t have a marketing department of 15 people, at the end we are men and women-orchestras.

What criteria do you use to evaluate the project of a new or unknown author?

As a producer, I have two readings: the first one as a spectator. That is, do I want to see this script turned into a film, would I go to see this film, do I want to spend at least three years wanting to tell this story? If the answer is yes, I move on to the second reading: will I be able to finance it? But, the thing is that the first one can happen and the second one can not. The opposite can also happen. These are the parameters that I set as filters. What usually happens with debut films is that it is very nice to mentor new directors, but this requires a lot of time because you are teaching them how the sector works: financing, timing, etc. And you can’t put more than one or two films like that a year because they require a lot of time and because the financing routes are very similar and we must be honest as producers and not have wonderful projects stuck in a drawer for a year or a year and a half and have that talent retained.

What percentage of funding is key to moving forward with a project?

Now that I teach at ESCAV and ECAM, I tell my students that if they want to be producers, forget about the heart. The Green Light should be when you have all the financing, including your fee as a producer. In the ideal world, the day you give “lights, camera, action!” you should have the financing of everything, including your own percentage of profit, in order to maintain the fixed structure and salaries of the production company. The success rate of a film is not always 100% and, therefore, you always have to invest a part of what you earn at risk to develop new projects, which would be the R&D of the production companies.

How important is the international dimension of a film today, from financing to sales and distribution?

There are projects that are natural for co-production and there are co-productions that are necessary for financing. When we shot “Mediterraneo: The Law of the See,” a story about the founding of Open Arms in Greece, it didn’t make sense that we didn’t have a Greek partner. That’s a natural co-production for me. With “Blackthorn,” which happened entirely in Bolivia, it didn’t make sense for us not to have a Bolivian partner, not only for financing but also for the convenience of field production. At Arcadia, 90% of the films we make are international co-productions, because of the need for financing and, above all, because of a European or international vision. I think we are one of the production companies that has received the most Euroimages European credits in the last ten years. We have co-produced with many European countries, especially France, and Latin American countries. But not all models need an international dimension. If you make a film just for Spanish audiences, you don’t have to look for international co-production.

How do you decide whether a film goes to a festival or not?

First, you have to decide if a film needs a festival, because not all films do. And then, it is the knowledge of the line up of the festivals, the previous trajectory of the director, the study of the competition in each festival and the agreement reached with the international sales agency. And it is also a matter of experience. One thing that makes a big difference is the production schedule. With “As bestas” we wanted to get to Cannes because of the French component, because of the actors, because of the director’s international career, and we adjusted the whole production schedule for that. We finished shooting on December 12 and in May it was in Cannes. It was very heroic because the post-production team had to run a lot to get there. In short, it’s not just about getting a film out and seeing where I’m going, but when you’re in the script and development phase you have to establish that “perfect storm”. Then, there are many conditioning factors and many things that we can’t control at each festival, but you always have to set the goal.

There is a new generation of Spanish female authors who are beginning to be recognized, such as Carla Simón, Pilar Palomero, Alauda Ruiz de Azúa or Celia Rico. Is this just a trend?

It is not a fad. It is the reflection of a generation. In my class there were already more girls than boys and now, that we are already in the 40, we have the visibility, age or maturity to be there and support women. In addition, it is something that has been encouraged by gender policies and public aid points. It is something that has come to stay. What I wish is that we no longer talk about gender, but about class. The next stigma to jump is to open the doors of the film industry to those who come from public universities, to people who come from a small town and from the working class so that they can get to produce or direct films, at the same level as those who come from private schools, which cost 10 or 12,000 euros a year. That’s our next fight.

Can we also speak of a new generation of women producers?

Not so much in executive producing and as partners in companies, but in technical production positions. But, there is also a new generation of women producers who support women directors and a different kind of storytelling. We now have a voice to decide.

How has the audiovisual industry evolved in Spain since you finished your degree in Audiovisual Communication almost 20 years ago?

I started working with the negative film in 2004 and since then everything has changed a lot: the format, post-production times, the entry of platforms, the digitization of theaters, etc. There have been many changes, although the craft of storytelling has been the same almost since the Greeks. For me the current moment is a time of great creativity and production, but the big challenge is distribution: where and how we see the content. There is a paradigm shift. I am one of the optimists who believe that theaters will never die, but another thing is what we are going to see in a movie theater. Now, we see big events and big movies, and the moviegoer audience that keeps the habit of going to the movies. The intermediate audience is the one that is suffering, as happened at the beginning of the 2000s, but the difference is that now it doesn’t die because they can reposition themselves and they can see their films on the platforms eight or ten weeks later.

You have accompanied several new authors in their first works, with which one have you come to feel like a mother and have you worked better?

That’s like telling a mother which child she loves the most. In terms of longevity, I’ve been with Pablo Berger since “Snow White” thirteen years ago. Pablo is like my older brother. With Celia Rico I’ve been a good friend for many years and we’ve already made two films, on our way to the third. Rodrigo Sorogoyen and I have been working together since “Mother”. They are people I love and who are very close to me.

Finally, your parents are from Caniles and you have spent many summers with them in the village. What potential does the province of Granada have as a film set? And what does it need to attract more film shoots?

Granada is my second homeland. I am from Girona and I am always comparing the two provinces. The province of Granada is very rich and has an incredible diversity of landscapes: coast, mountains, high plateau, Sierra Nevada, the city of Granada itself, etc. There are very few provinces in Spain that can offer all this. The only thing that Granada, and Andalusia in general, needs is to give an extra element to producers, such as a tax incentive, as the Basque Country, Navarre and the Canary Islands have already done, and in general, to increase the facilities for filming.